주메뉴

- About IBS 연구원소개

-

Research Centers

연구단소개

- Research Outcomes

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Particle Theory and Cosmology Group)

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Cosmology, Gravity and Astroparticle Physics Group)

- Center for Exotic Nuclear Studies

- Center for Artificial Low Dimensional Electronic Systems

- Center for Underground Physics

- Center for Axion and Precision Physics Research

- Center for Theoretical Physics of Complex Systems

- Center for Quantum Nanoscience

- Center for Van der Waals Quantum Solids

- Chemistry

- Life Sciences

- Earth Science

- Interdisciplinary

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research(Neuro Technology Group)

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research(Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience Group)

- Center for Algorithmic and Robotized Synthesis

- Center for Genome Engineering

- Center for Nanomedicine

- Center for Biomolecular and Cellular Structure

- Center for 2D Quantum Heterostructures

- Center for Quantum Conversion Research

- Institutes

- Korea Virus Research Institute

- News Center 뉴스 센터

- Career 인재초빙

- Living in Korea IBS School-UST

- IBS School 윤리경영

주메뉴

- About IBS

-

Research Centers

- Research Outcomes

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Particle Theory and Cosmology Group)

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Cosmology, Gravity and Astroparticle Physics Group)

- Center for Exotic Nuclear Studies

- Center for Artificial Low Dimensional Electronic Systems

- Center for Underground Physics

- Center for Axion and Precision Physics Research

- Center for Theoretical Physics of Complex Systems

- Center for Quantum Nanoscience

- Center for Van der Waals Quantum Solids

- Chemistry

- Life Sciences

- Earth Science

- Interdisciplinary

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research(Neuro Technology Group)

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research(Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience Group)

- Center for Algorithmic and Robotized Synthesis

- Center for Genome Engineering

- Center for Nanomedicine

- Center for Biomolecular and Cellular Structure

- Center for 2D Quantum Heterostructures

- Center for Quantum Conversion Research

- Institutes

- Korea Virus Research Institute

- News Center

- Career

- Living in Korea

- IBS School

News Center

|

Genome edited plants, without DNA- CRISPR-Cas9 RNP technique in plants could be the key to feeding the planet - October 19, 2015 The public and scientists are at odds over the safety of genetically modified (GM) food. According to a January 2015 Pew Research Center report, only 37% of the public believe that GM foods are safe which is in stark contrast to the support from 88% of scientists. There is concern that adding DNA of different species will lead to unintended, undesirable consequences. Scientists at the IBS Center for Genome Engineering in South Korea have created a way to genetically modify plants using CRISPR-Cas9 without the addition of DNA. Because no DNA is used in this process, the resulting genome-edited plants could likely be exempt from current GMO regulations and given a warmer reception by the public. What makes this work so groundbreaking is that these genetic modifications look just like genetic variations resulting from the selective breeding that farmers have been doing for millennia. IBS Director of the Center for Genome Engineering Jin-Soo Kim explains that “the targeted sites contained germline-transmissible small insertions or deletions that are indistinguishable from naturally occurring genetic variation.”

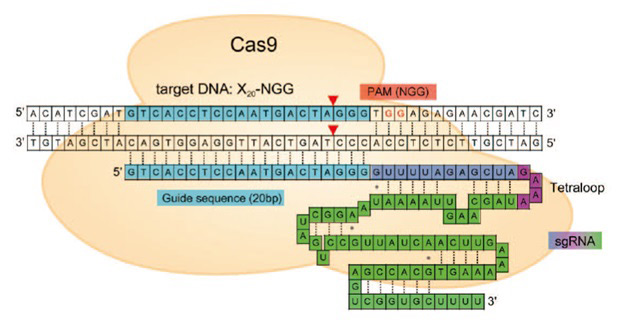

CRISPR is an acronym for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat, which refers to the unique repeated DNA sequences found in bacteria and archaea. CRISPR is now used widely for genome editing. What’s crucial in genetic engineering is for the gene editing tool to be accurate and precise, which is where CRISPR-Cas9 excels. CRISPR-Cas9 uses a single guide RNA (sgRNA) to identify and edit the target gene and Cas9 (a protein) then cleaves the gene, resulting in site-specific DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). When the cell repairs the DSB, the resulting fix is the intended genetic edit. The beauty of this research is that the IBS research team has elevated the process and no longer uses DNA, being unshackled from GMO regulations. To do this, purified Cas9 protein was mixed with sgRNAs targeting specific genes from three plant species to form preassembled ribonucleoproteins (RNPs). The IBS team used these Cas9 RNPs to transfect several different plants including tobacco, lettuce and rice to achieve targeted mutagenesis in protoplasts. To test the efficacy of this process, the team delivered Cas9 RNPs to the protoplasts of the test plant species, and found Cas9 RNP-induced mutations 24 hours after transfection. These newly cloned lettuce cells showed no mosaicism which led the researchers to believe that the RGEN RNP may have cleaved the target site immediately after transfection and the indels occurred before cell division was completed.

Finally, the team demonstrated that RGEN-induced mutations were maintained after regeneration. Using a Cas9 RNP, they disrupted a gene in lettuce called Brassinosteroid Insensitive 2 (BIN2) which regulates the signaling of brassinosteroid, a class of steroid hormones responsible for a wide range of physiological processes in the plant life cycle, including growth. They found that after cell division the lettuce cells maintained the disruption of the gene with a frequency of 46%. Importantly, there were no off-target indels. They grew full plants from the seeds of these genome edited and regenerated plants, which had the mutation from the previous generation. They were able to definitively show that Cas9 RNPs can be used to genetically modify plants, which Jin-Soo Kim points out, “paves the way for the widespread use of RNA-guided genome editing in plant biotechnology and agriculture.” The IBS team’s technique of genome editing without inserting DNA could be revolutionary for the future of the seed industry. The RGEN RNP process will enable us to produce plants that are heartier and more suited to climate change in order to feed Earth’s increasing population. Currently European Union GMO regulations don’t allow for food with added DNA. Since the Cas9 RNP technique does not use DNA, it may be able to avoid being in violation of these rules. In addition, using Cas9 RNP is cheaper, faster and more accurate to apply to plants than previous breeding techniques (like radiation-induced mutations). Large agribusiness companies have been able to afford the time and money necessary to create seeds for genetically modified food, but the Cas9 RNP technique could allow for a more decentralized gene-edited seed production industry. This process is ready for use to bolster plant output and create heartier crops in foods like tomatoes and lettuce. The application of the Cas9 RNP gene editing technique could be the next step in ending food shortages. By Daniel Kopperud Notes for editors - References - Media Contact - About the Institute for Basic Science (IBS)

|

|||

|

|

| Next | |

|---|---|

| before |

- Content Manager

- Public Relations Team : Yim Ji Yeob 042-878-8173

- Last Update 2023-11-28 14:20