주메뉴

- About IBS 연구원소개

-

Research Centers

연구단소개

- Research Outcomes

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Center for Underground Physics

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe (Particle Theory and Cosmology Group)

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe (Cosmology, Gravity and Astroparticle Physics Group)

- Dark Matter Axion Group

- Center for Artificial Low Dimensional Electronic Systems

- Center for Theoretical Physics of Complex Systems

- Center for Quantum Nanoscience

- Center for Exotic Nuclear Studies

- Center for Van der Waals Quantum Solids

- Center for Relativistic Laser Science

- Chemistry

- Life Sciences

- Earth Science

- Interdisciplinary

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research (Neuro Technology Group)

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research (Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience Group)

- Center for Algorithmic and Robotized Synthesis

- Center for Nanomedicine

- Center for Biomolecular and Cellular Structure

- Center for 2D Quantum Heterostructures

- Institutes

- Korea Virus Research Institute

- News Center 뉴스 센터

- Career 인재초빙

- Living in Korea IBS School-UST

- IBS School 윤리경영

주메뉴

- About IBS

-

Research Centers

- Research Outcomes

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Center for Underground Physics

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe (Particle Theory and Cosmology Group)

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe (Cosmology, Gravity and Astroparticle Physics Group)

- Dark Matter Axion Group

- Center for Artificial Low Dimensional Electronic Systems

- Center for Theoretical Physics of Complex Systems

- Center for Quantum Nanoscience

- Center for Exotic Nuclear Studies

- Center for Van der Waals Quantum Solids

- Center for Relativistic Laser Science

- Chemistry

- Life Sciences

- Earth Science

- Interdisciplinary

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research (Neuro Technology Group)

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research (Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience Group)

- Center for Algorithmic and Robotized Synthesis

- Center for Nanomedicine

- Center for Biomolecular and Cellular Structure

- Center for 2D Quantum Heterostructures

- Institutes

- Korea Virus Research Institute

- News Center

- Career

- Living in Korea

- IBS School

News Center

| Title | Plants Get a Brace to Precisely Shed Flowers and Leaves | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Embargo date | 2018-05-04 00:00 | Hits | 3658 |

| Research Center |

Center for Plant Aging Research |

||

| Press release | |||

| att. | |||

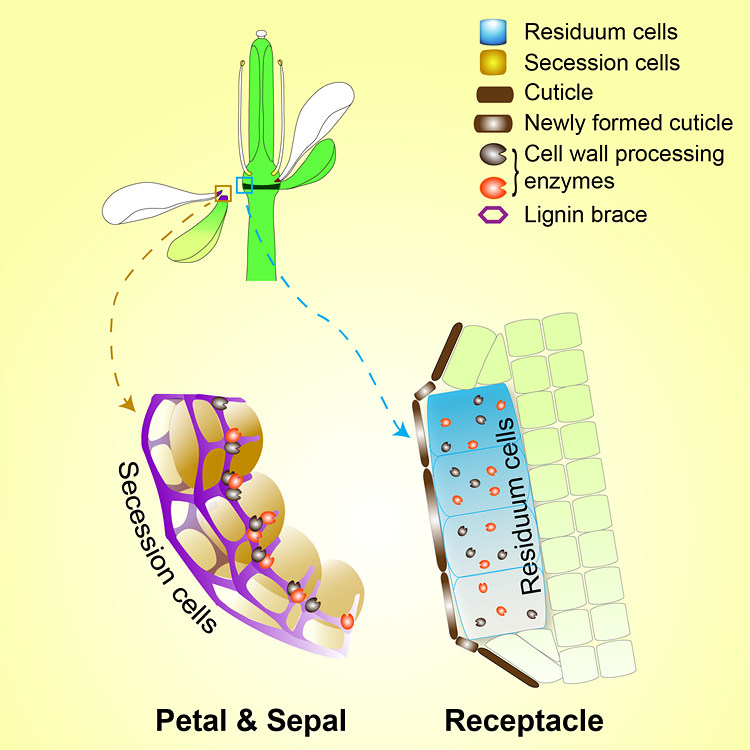

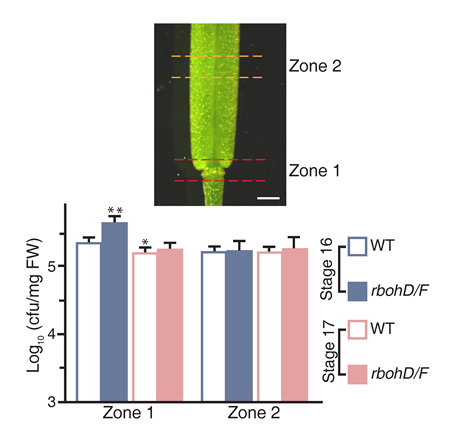

Plants Get a Brace to Precisely Shed Flowers and Leaves- A study on how petals fall, and plants cope with the lost. To protect reproductive organs from bacterial and external harm, plants create a special brace to assure an accurate detaching process and a coating to seal the open cut left by the shedding. - Spring. As a delicate wind blows, pink cherry blossom petals leave branches by flying in the air. It sounds like the setting of a romantic movie, but it is actually the research topic of a team at Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology (DGIST) and the Institute for Basic Science (IBS). The team is keen on studying this as the mechanism of such process is far from clear. Spoiling the magic, each of the falling petals leaves behind a little open cut, which might be prone to infection. The same happens when plants shed leaves, fruits, and seeds. Researchers at the Department of New Biology at DGIST and the Center for Plant Aging Research within IBS, have just reported in Cell how plants regulate the detachment process and protect themselves. As shedding is closely associated with a plants’ life cycle, this is a topic of substantial interest to improve crop and fruit production. In order for leaves, flowers and fruits to drop, specific proteins, known as cell wall processing enzymes, need to precisely act to degrade the cell wall between the cells, facilitating the cell-to-cell detachment. Similar to a plant wound, the opening must be quickly re-sealed to avoid access of bacteria and harmful substances, but in comparison to a wound, the team found out that plants use a different mechanism to seal the opening. The detachment spot (abscission zone) was found to consist of two neighboring cell types: residuum cells (RECs) remaining on the plant and secession cells (SECs) in flowers, leaves, etc. “The separation must be precise and minimal as the process transiently increases vulnerability to environmental peril,” explains June M. Kwak, leading author of the study.

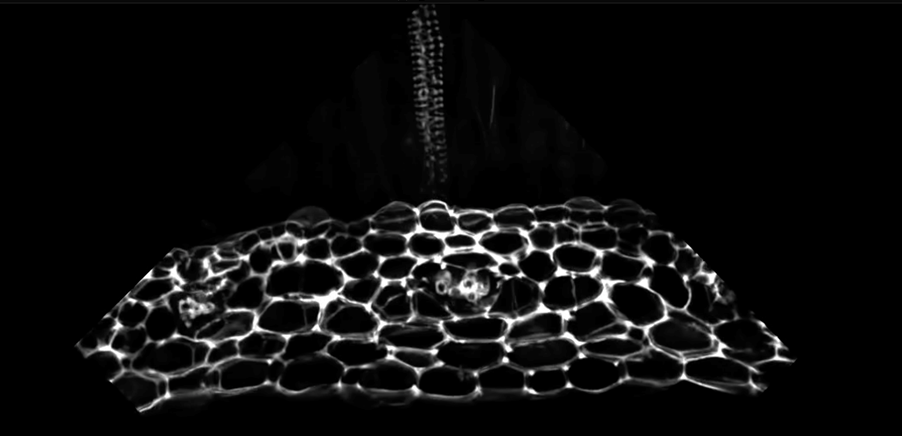

DGIST and IBS researchers used the classic plant model, Arabidopsis thaliana, to investigate how plants overcome the physical constraint of cell walls, and accomplish organ abscission. The two cell types in the abscission zone display different cellular activities and architectures. In particular, SECs form two to three layers of lignin with a honeycomb structure. On the detachment area, lignin acts as a molecular brace that may hold individual SECs together when they shed from the plant. In addition, it might limit cell wall processing enzymes to a confined area, allowing precision abscission. “Because of the light and rigid property of the honeycomb architecture, it is perhaps unsurprising that we find plant cells have evolved such a structure to accomplish a potentially dangerous cellular process with great accuracy,” explains Kwak.

Immediately after SECs are gone with the wind, RECs accumulate a thin cell wall, which is vulnerable to infections and external harm. To protect the newly formed cell surface, RECs shield themselves with a protective coating made of cutin, which is responsible for the surface protection against pathogens. This indicates that non-epidermal RECs change identity turning into epidermal cells. This is particularly interesting as the specification of epidermal cell identity was thought to be restricted to the embryonic stage.

The formation of this cutin layer is distinct from the mechanism of plant wound healing. The latter provides a protecting barrier made of cork rather than cutin. How the two processes are related is still mysterious. And while looking for the answer, let’s enjoy the beautiful blooming of flowers and change of seasons. Letizia Diamante Notes for editors - References - Media Contact - About the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) |

|||

|

|

|||

| Next | |

|---|---|

| before |

- Content Manager

- Communications Team : Kwon Ye Seul 042-878-8237

- Last Update 2023-11-28 14:20