- New way to generate extreme-ultraviolet emissions could open the way for ultrafast spectroscopy, high-resolution imaging and next-generation lithography -

A team at the Center for Relativistic Laser Science, within the Institute for Basic Science (IBS), has found a completely new way to generate extreme-ultraviolet emissions, that is light having a wavelength of 10 to 120 nanometers. Published in Nature Photonics, this method is expected to find applications in imaging with nanometer resolution, next-generation lithography for high precision circuit manufacturing, and ultrafast spectroscopy.

Until recently, the motion of electrons at the atomic scale was inscrutable and inaccessible. Lasers with ultrafast pulses have provided tools to monitor and control electrons with sub-atomic resolution, and has allowed scientists to get familiar with real-time electron dynamics. One of the new possibilities is to use these laser pulses to generate customized emissions.

Emission are the outcome of meandering excited electrons. When a strong laser light shines on helium atoms, their electrons are free to temporarily escape from their parent atoms. As the laser is turned off, on the way back, these meandering electrons could either recombine with their parents straight away, or keep on "floating" nearby. The fast return of electrons is part of the high-harmonic generation, while the "floating" is called frustrated tunneling ionization (FTI). In both cases, the net result is the emission of light with a specific wavelength. In this study, IBS researchers have produced coherent extreme-ultraviolet radiation via FTI for the first time.

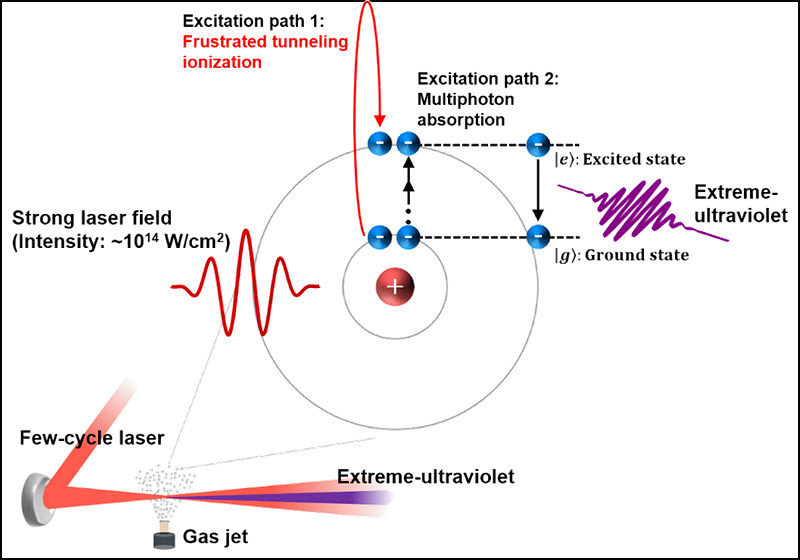

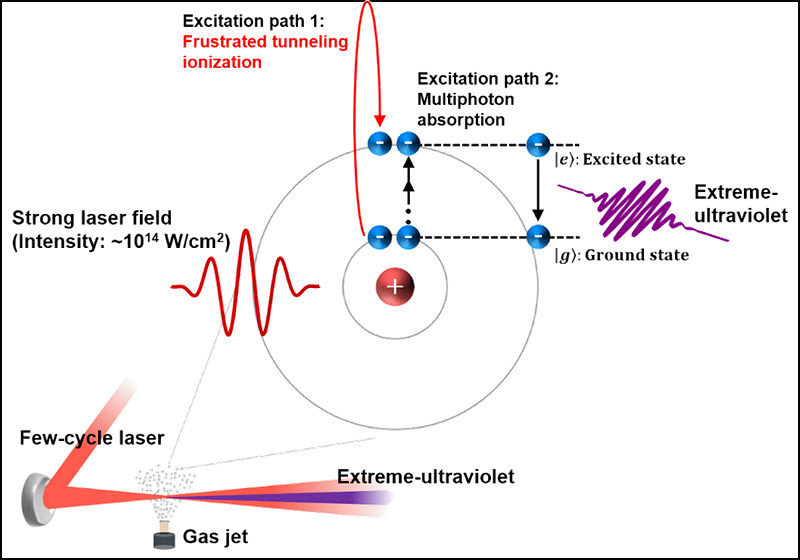

Figure 1: The electron’s journey. When a strong laser shines on helium gas atoms, electrons transition from ground to excited state. The excited atoms then emit light corresponding to the energy difference between the two states and the electrons come back to their original ground state. The general believe is that this happens when the atoms absorb several light particles (photons). However, according to this research, the journey of the electrons can take a different path: when the intensity of the laser field is high, the electrons can experience frustrated tunneling ionization (FTI): rather than coming back straight away to the ground state, they can remain floating near the atom, in the so-called Rydberg states. In this case, the emitted light depends on the energy difference between Rydberg and ground states.

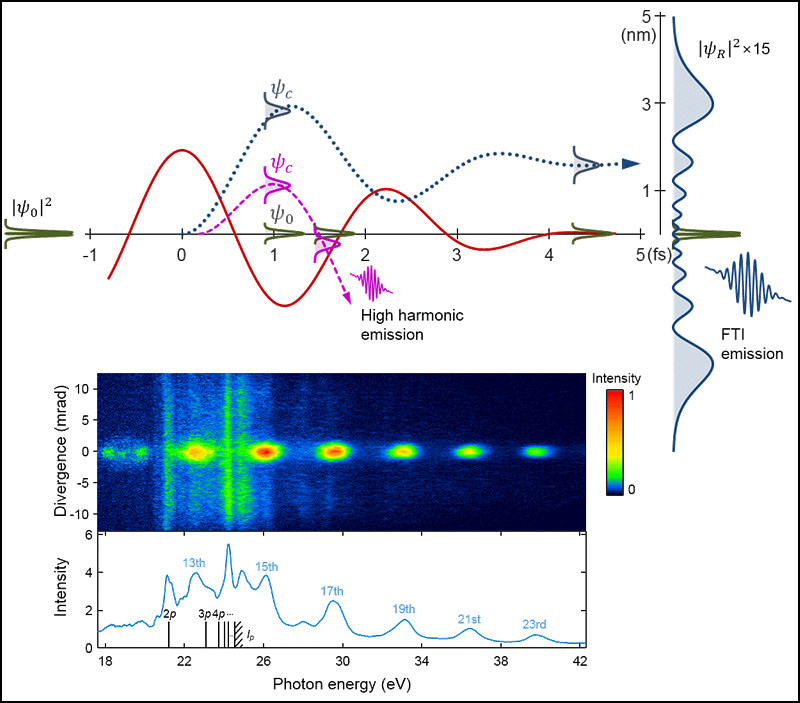

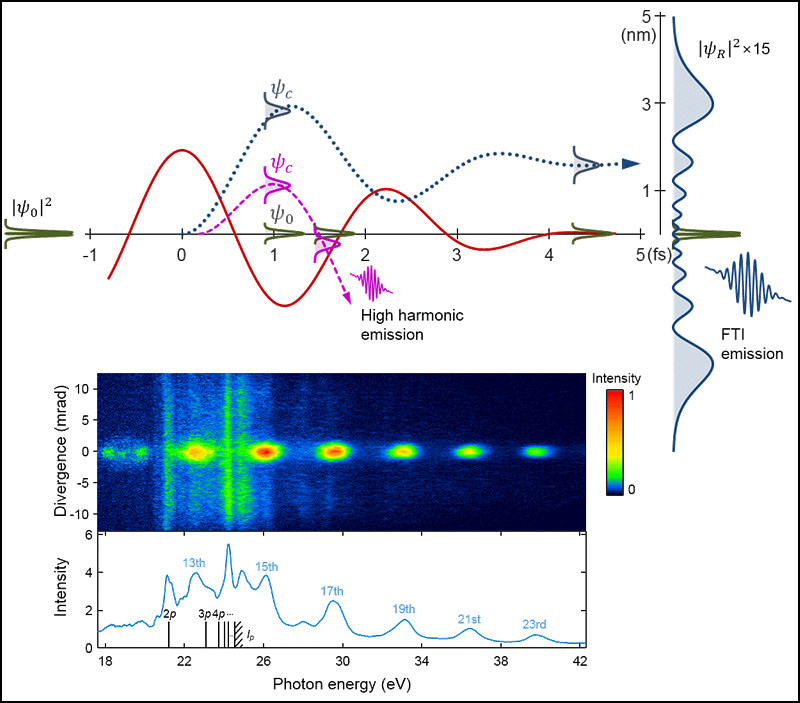

Figure 2: Frustrated tunneling ionization (FTI) or high harmonic generation? The figure on the top compares FTI (blue dotted line) with high harmonic generation (purple dashed lines). When a laser field (red solid line) is applied to a helium atom, an electron becomes free. Depending on the timing, the free electron accelerates with different trajectories. In the well-known case of high harmonic generation, the electron recombines with its parent atom, and the periodic repetition of this process generates bursts of light emission having the spectrum at regular intervals, as shown in the lower image. In the case of FTI, once the effect of the laser is gone, the electrons reach a Rydberg state. FTI-generated extreme-ultraviolet radiation shows a fairly large divergence angle and narrow spectral width.

IBS researchers were able to control the trajectory of electrons by manipulating characteristics of the laser pulse. In FTI, the electrons travel a much longer trajectory than in high harmonic generation, and thus are more sensitive to variations of the laser pulse. For example, the team were able to control the direction of the emitted radiation by playing with the wavefront rotation of the laser beam (using spatially chirped laser pulses).

"We used IBS' state-of-the-art laser technology to control the movement of the meandering electrons. We could identify a completely new coherent extreme-ultraviolet emission that was generated. We understood the fundamental mechanism of the emission, but there are still many things to investigate, such as phase matching and divergence control issues. These issues should be solved to develop a strong extreme-ultraviolet light source. Also, it is an interesting scientific issue to see whether the emission is generated from molecules, as it could provide information on the molecular structure and dynamics," explains the group leader, KIM Kyung Taec.

Letizia Diamante

Notes for editors

- References

Hyeok Yun, Je Hoi Mun, Sung In Hwang, Seung Beom Park, Igor A. Ivanov, Chang Hee Nam, Kyung Taec Kim. Coherent extreme ultraviolet emission generated through frustrated tunneling ionization. Nature Photonics (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41566-018-0255-8

- Media Contact

For further information or to request media assistance, please contact: Mr. Kyungyoon Min, Head of Communications Team, Institute for Basic Science (IBS) (+82-42-878-8156, kymin@ibs.re.kr); or Ms. Carol Kim, Global Officer, Communications Team, IBS (+82-42-878-8133, clitie620@ibs.re.kr).

- About the Institute for Basic Science (IBS)

IBS was founded in 2011 by the government of the Republic of Korea with the sole purpose of driving forward the development of basic science in South Korea. IBS has launched 28 research centers as of August 2018. There are nine physics, one mathematics, six chemistry, eight life science, one earth science, and three interdisciplinary research centers.