주메뉴

- About IBS 연구원소개

-

Research Centers

연구단소개

- Research Outcomes

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Particle Theory and Cosmology Group)

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Cosmology, Gravity and Astroparticle Physics Group)

- Center for Exotic Nuclear Studies

- Center for Artificial Low Dimensional Electronic Systems

- Center for Underground Physics

- Center for Axion and Precision Physics Research

- Center for Theoretical Physics of Complex Systems

- Center for Quantum Nanoscience

- Center for Van der Waals Quantum Solids

- Chemistry

- Life Sciences

- Earth Science

- Interdisciplinary

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research(Neuro Technology Group)

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research(Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience Group)

- Center for Algorithmic and Robotized Synthesis

- Center for Genome Engineering

- Center for Nanomedicine

- Center for Biomolecular and Cellular Structure

- Center for 2D Quantum Heterostructures

- Center for Quantum Conversion Research

- Institutes

- Korea Virus Research Institute

- News Center 뉴스 센터

- Career 인재초빙

- Living in Korea IBS School-UST

- IBS School 윤리경영

주메뉴

- About IBS

-

Research Centers

- Research Outcomes

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Particle Theory and Cosmology Group)

- Center for Theoretical Physics of the Universe(Cosmology, Gravity and Astroparticle Physics Group)

- Center for Exotic Nuclear Studies

- Center for Artificial Low Dimensional Electronic Systems

- Center for Underground Physics

- Center for Axion and Precision Physics Research

- Center for Theoretical Physics of Complex Systems

- Center for Quantum Nanoscience

- Center for Van der Waals Quantum Solids

- Chemistry

- Life Sciences

- Earth Science

- Interdisciplinary

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research(Neuro Technology Group)

- Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research(Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience Group)

- Center for Algorithmic and Robotized Synthesis

- Center for Genome Engineering

- Center for Nanomedicine

- Center for Biomolecular and Cellular Structure

- Center for 2D Quantum Heterostructures

- Center for Quantum Conversion Research

- Institutes

- Korea Virus Research Institute

- News Center

- Career

- Living in Korea

- IBS School

News Center

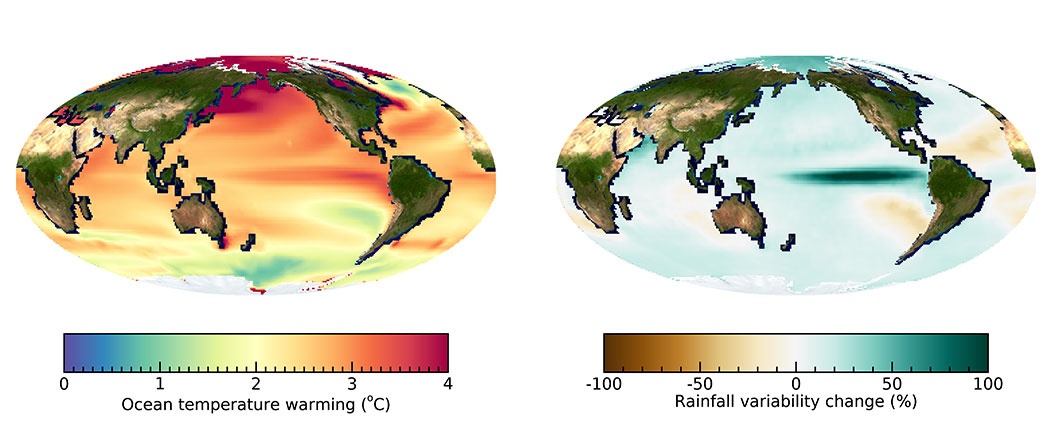

Future ocean warming boosts tropical rainfall extremesOcean warming predicted to cause a twofold increase in amplitude of rainfall fluctuations over the tropical Pacific The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the most energetic naturally occurring year-to-year variation of ocean temperature and rainfall on our planet. The irregular swings between warm and wet “El Niño” conditions in the equatorial Pacific and the cold and dry “La Niña” state influence weather conditions worldwide, with impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and economies. Climate models predict that the difference between El Niño- and La Niña-related tropical rainfall will increase over the next 80 years, even though the temperature difference between El Niño and La Niña may change only very little in response to global warming. A new study published in Communications Earth & Environment uncovers the reasons for this surprising fact.

Using the latest crop of climate models, researchers from the IBS Center for Climate Physics at Pusan National University, the Korea Polar Research Institute, the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, and Environment and Climate Change Canada, worked together to unravel the mechanisms involved. “All climate models show a pronounced intensification of year-to-year tropical rainfall fluctuations in response to global warming.” says lead author Dr. Kyung-Sook Yun from the IBS Center for Climate Physics (Image, right panel). “Interestingly the year-to-year changes in ocean temperature do not show such a clear signal. Our study therefore focuses on the mechanisms that link future ocean warming to extreme rainfall in the tropical Pacific”, she goes on to say. The research team found that the key to understanding this important climatic feature lies in the relationship between tropical ocean surface temperature and rainfall. There are two important aspects to consider: 1) the ocean surface temperature threshold for rainfall occurrence, and 2) the rainfall response to ocean surface temperature change, referred to as rainfall sensitivity. “In the tropics, heavy rainfall is typically associated with thunderstorms and deep clouds shaped like anvils. These only form once the ocean surface is warmer than approximately 27.5 degrees Celsius or 81 degrees Fahrenheit in our current climate”, says co-author Prof. Malte Stuecker from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. This ocean surface temperature threshold for intense tropical rainfall shifts towards a higher value in a warmer world and does not contribute directly to an increase in rainfall variability. “However, a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture which means that when it rains, rainfall will be more intense. Moreover, enhanced warming of the equatorial oceans leads to upward atmospheric motion on the equator. Rising air sucks in moist air from the off-equatorial regions, which can further increase precipitation, in case other meteorological conditions for a rain event are met.” says co-lead author Prof. June-Yi Lee from IBS Center for Climate Physics. This increase in rainfall sensitivity is the key explanation why there will be more extreme ENSO-related swings in rainfall in a warmer world. Notes for editors - References - Media Contact - About the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) - About ICCP |

|||

|

|

| Next | |

|---|---|

| before |

- Content Manager

- Public Relations Team : Yim Ji Yeob 042-878-8173

- Last Update 2023-11-28 14:20